The Romans crucified their victims naked.

Indeed, the Gospels may even imply this when noting that soldiers cast lots for Christ’s clothing. Still, the thought of a naked Jesus splayed out before the world is uncomfortable to us. And rightly so. You will not find this painting in your Christian bookstore.

Along these lines, I recall (years ago) a fellow student asking a professor about the possibility that Christ hung naked on the cross. The teacher was incensed. “Of course not! To even think so is offensive!”

While I appreciated the concern for modesty, I remember thinking that the whole nailing-an-innocent-man-to-a-cross part was pretty offensive too. Yet it happened.

To reflect on this nakedness, however, does seem crass, unless there is some insight to be gained. And I think there is.

It has to do with bodies, shame, and those who have been made to feel less than human.[1]

DEFINING SHAME

According to psychologists, we feel guilt for wrongs we have done. Yet we feel shame for who we are at some deep level. The concepts are related, but distinct.

Unfortunately, while guilt can be atoned for by punishment or making amends, shame clings to us more tenaciously. It lodges in our minds and in our marrow. It is the difference between “I have done wrong” and “I am wrong.”[2]

For Gershen Kaufman:

To feel shame is to feel seen in a painfully diminished sense. The self feels exposed both to itself and to anyone present. [It] is the piercing awareness of ourselves as fundamentally deficient in some vital way as a human being.[3]

While certain forms of shame may be warranted, this pervasive kind is deadly.

SHAME AND NAKEDNESS

In the Bible, shame is linked to nakedness. It didn’t start this way (Gen. 2.25), but when Adam eats the fruit he feels exposed. He was never clothed, of course, but now he feels it. So he seeks to cover himself. Enter fig leaves. In fact, the stated fear is not punishment, but being seen undressed.

“I heard you in the garden, and I was afraid because I was naked; so I hid” (Gen. 3.10).

The problem is shame, but the feeling is a body that we want to hide.

BODY SHAME

Today, the trend continues. In our culture, a common cause of shame is the body itself, especially as it fails to conform to rigid standards of perfection: models, magazines, ubiquitous pornography, and the crucible of comparison. These days, not even the perfect people are perfect enough, as evidenced by the need to airbrush them.

So while the apostle Paul once assumed that “no one ever hated his own body” (Eph. 5.29), our culture shouts back: “Speak for yourself!”

It is unsurprising then that so many of our shame words relate to the body.

- fat,

- weak,

- pudgy,

- plain,

- pock-marked,

- bald,

- scarred,

- flat,

- freak,

- repulsive,

- and many racial slurs I will not write.

Whatever postmodernity is, it is definitely post-Eden.

SEXUAL SHAME

Then there is the realm of sexual shame.

The statistics are staggering: Twenty-five percent of girls will be sexually abused before they turn eighteen. One in five women will be raped, and 325,000 children will be victims of sex trafficking this year.

For many of us, the numbers include faces that we recognize. Indeed, the pain becomes more personal when listening, as I have, to a student say the following: “I was raped by my first boyfriend. We met at church. No one believed me.”

Shame.

Increasingly, the “Hunting Ground” for sexual assaults are college campuses (see here), where a mix of alcohol, partying, and attempts to hush or blame the victims often combine to add one shame upon another. Over such campuses, the question tolls like a funeral bell: “Where can I go to be rid of my disgrace?”

And that is not to mention the myriad of consensual encounters that leave one or both persons feeling objectified, used, and cast aside.

It is not called the “walk of shame” for nothing.

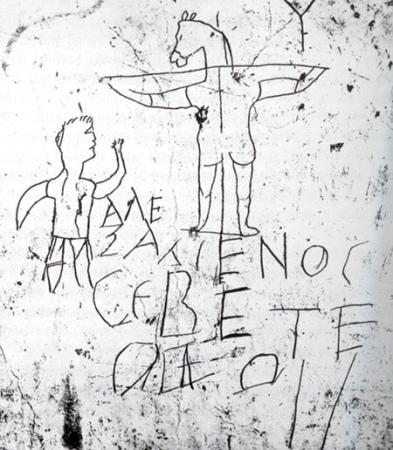

CHRISTUS NUDUS

But what does this have to do with the shameful nudity of Christ upon the cross?

Everything.

As one scholar writes:

The whole point of Roman crucifixion was to reduce the victim to the status of a thing, stripping him of every vestige of human dignity, in order to discourage any challenging of the might of Rome.[4]

The key idea is this: We do not have a Jesus who merely bears our guilt and sin. Nor merely one who conquers death and devils. Nor merely one who loves without exceptions.

In addition to all this, Christ also enters into our deepest experience of shame and nakedness. He was mocked and laid bare not only before tormenters, but before his weeping mother! It does not get more shameful.

So hear this: To the bullied teen who cowers in the bathroom stall, to the victim of sexual assault who feels blamed for someone else’s crime, and to all others made to feel the weight of heaped-on shame, Christ says: “I KNOW.” I have been there.

I am Christus nudus (“the naked Christ”), not merely Christus victor (“Christ the victor”).

The cross is “God’s shame-bearing symbol for the world.”[5]

Upon it, the second Adam assumed the nakedness of the first, for as Gregory of Nazianzen wrote: “The unassumed is the unhealed.” We need a God who bears our shame. And we have one in the naked Christ.

CLOTHED WITH CHRIST

But it does not end there.

After the resurrection, the New Testament pictures salvation as being clothed. Yet the clothing is not of earthly garments, but “with Christ” (Rom. 13.14). Paul saw this as taking place at baptism (Gal. 3.27).

Thus the early church even began what may seem like a strange practice.

Converts were baptized naked in imitation of a Christ who hung naked on the cross. In response to this, Saint Jerome’s (347–420 AD) oft-repeated motto for the Christian lifestyle read as follows:

“nudus nudum Jesum Sequi” (naked to follow a naked Christ).

Because of Jesus, the metaphor of nakedness was transformed from a mark of shame to a metaphor of purity, innocence, and life-giving vulnerability (on that last bit, see here).

This is so because, on the cross, Christ not only bore our shame, he “scorned” it (Heb. 12.2).

This is indeed good news.

Christus nudus; Christus victor.

———–

[1] For a mountain of research on this topic, see the published doctoral dissertation of Dan Lé, The Naked Christ: An Atonement Model for a Body Obsessed Culture (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2012).

[2] See T. Mark McConnell, “From ‘I Have Done Wrong’ to ‘I am Wrong’,” in Locating Atonement: Explorations in Constructive Dogmatics, eds. Oliver Crisp and Fred Sanders (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2015).

[3] Gershen Kaufman, Shame: The Power of Caring (Cambridge, MA: Schenkman, 1985), ix–x.

[4] Philip Cunningham, Jesus and the Evangelists (New York: Paulist, 1988), 187.

[5] Robert Albers, “The Shame Factor: Theological and Pastoral Reflections Relating to Forgiveness,” Word & World 16:3 (June 1, 1996), 352.

Hello Joshua

I just came across your article and enjoyed it. Thanx. I have been looking at this ‘body shame’ and it is totally un-biblical! What is being taught by the religious people about what happened in the Garden of Eden is false… I have summarized this in a short article which is too long to paste here but we have been grossly misled by the religious and political crowd when ‘Christianity’ became the belief system of the Roman Empire. You will not find a single teaching against basic nudity in the whole of the Bible. People confuse nakedness with sexual sin, which is something totally different!

LikeLike

Hey there, I’m not exactly certain how I came across this. But I’d like to Thankyou for writing it, it really blessed me this morning and I am grateful to have a deeper revelation of the price Jesus paid for a ‘wretch like me’. It did move me to tears and a new thankfulness towards Jesus.

May God Bless you,

Thankyou.

LikeLike

You’re welcome!

LikeLike