A bombshell landed on the literary world last year after the death of Cormac McCarthy, the man who had been, arguably, America’s greatest living novelist.

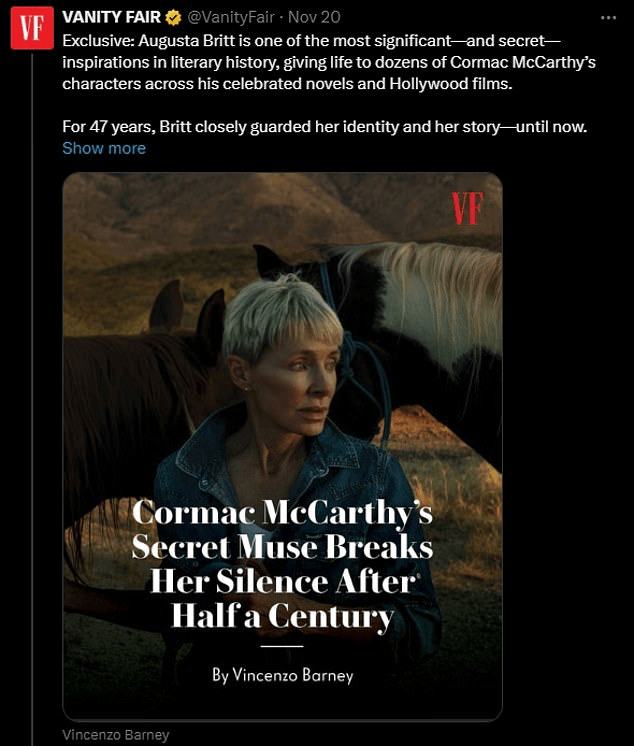

The shock was not McCarthy’s passing (he was 89), but a Vanity Fair article by Vincenzo Barney that broke news of a nearly fifty-year relationship with a woman named Augusta Britt—the “secret muse” whose life and personality inspired many of McCarthy’s greatest characters, most of whom were male.

“I’m about to tell you the craziest love story in literary history,” the article began.

The short summary put it this way:

Augusta Britt would go on to become one of the most significant—and secret—inspirations in literary history, giving life to many of McCarthy’s most iconic characters across his celebrated novels and Hollywood films. For 47 years, Britt closely guarded her identity and her story. Until now.

A firestorm ensued, in part, because the relationship began when Britt was just 16 and McCarthy 42. She met him by a hotel pool, while on the run from abuse within the foster system–a Colt revolver on her hip, his book in her hand. “Are you going to shoot me, little lady?” was allegedly McCarthy’s question.

Though Britt maintains that McCarthy saved her life, reactions to the article have understandably been mixed. “Let’s be honest with ourselves,” read a headline from The Guardian, “Cormac McCarthy groomed a teenage girl.”

I read the Vanity Fair piece back when it came out, which raises the question: Why write about it now, months later?

To be honest, a particular phrase sometimes gets lodged in my mind, long after I have read a book or article, and that’s essentially what happened here.

I’ve had a long relationship with McCarthy’s novels (see here and here), and he is undoubtedly one of the great writers of his generation. You can’t read books like The Road or Blood Meridian and not be struck by the power of his prose, the Christ-haunted characters, and the desert landscapes that seem to whirl and pulse in ways unmatched by any other author.

Unfortunately, great writers are not always great people. And in some cases, the relation seems to run the other way.

Here, then, is Augusta Britt’s assessment that stuck with me about McCarthy’s later years:

But as his characters started becoming better humans, in Britt’s view, McCarthy, whom she always thought of as a great man, did not. As he dined with celebrities and reinvented himself in Santa Fe as a formidable intellectual … he turned his back on his oldest friends. “He felt he’s wasted the last years of his life,” Britt says.

I can’t say if that’s true. (After all, running off to Mexico with a underage girl seems to work against the hypothesis that McCarthy’s moral compass became skewed primarily in his later years.)

Nonetheless, the potential divergence between one’s work and life strikes me as both interesting and relevant for all of us.

Why might one’s characters be getting better, while one’s character is either stalled or getting worse?

I’ve been struggling with a term to define the tendency, beyond mere hypocrisy. In the realm of spiritual formation, we might call this compartmentalization, rationalized regression, or a sort of moral transference. Psychologically speaking, transference involves the redirection to a substitute, often a therapist, of emotions or experiences that are (or ought to be) one’s own: in this case, from one’s character, to one’s characters.

Again, I don’t know if that happened with McCarthy, but I’m quite certain it’s a temptation for us.

Consider:

“While his sermons were getting better, his inner life was getting worse.”

“While her performance evaluations were getting better, her spiritual health was growing worse.”

“While his resume was getting better, his parenting was getting worse.”

If there’s a lesson here, perhaps it’s this: substitutionary sanctification is a dead end.

To amend one of my favorite verbal amulets from L. M. Sacasas, “[moral work] cannot be outsourced”–whether to AI agents or to characters between the pages of a book.

Hello friends. Please subscribe on the homepage to receive these posts by email. This is especially helpful since I’ve decided (mostly) to uncouple the blog from social media. Thanks for reading. ~JM