What should be the church’s posture toward the world?

The challenge, as with bodily posture (hunched shoulders, rounded back, neck forward), is that posture solidifies at a subconscious level, without us noticing. (Did you just sit up straighter?)

To this point, I recently reread an excellent essay by the theologian, Natalie Carnes with the following subtitle: “Reconsidering the Church-World Divide” (here). She begins by drawing attention to other articles with titles like this: “World versus Church: Who Is Winning?” (…a line that could only be more cringeworthy if read by Howard Cosell).

I won’t rehash Carnes’ full argument, but it includes a helpful reminder that Scripture contains BOTH protagonistic and antagonistic passages on the church-world relationship. Both “for” and “against.”

Church Against World

For instance,

“You adulterous people, don’t you know that friendship with the world means enmity against God?”

~James 4:4

Or even stronger,

“Do not love the world or anything in the world. If anyone loves the world, love for the Father is not in them.”

~1 John 2:15

Church For the World

On the other hand, numerous passages reveal God’s radical heart for the world, which calls us to a similar “for-ness”: loving, serving, and practicing incarnate presence.

Most famously,

“God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life. For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him.”

~John 3:16

And this,

“God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ, not counting people’s sins against them. And he has committed to us the message of reconciliation.”

~2 Corinthians 5:19

The following line from 1 John is even more interesting since it comes in the same book (above) that contains, arguably, the strongest anti-world prooftext:

“He [Jesus] is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not only for ours but also for the sins of the whole world.”

~1 John 2:2

Pro or Contra?

So… which is it?

Should the church be for or against the world?

It has long been acknowledged that different passages can mean different things while using the same word. Hence, “world” (cosmos) is a bit like “flesh” in its varied biblical meaning. In some cases, it means God’s good-but-fallen creation, loved and reconciled by Christ’s work. In others, it refers to a willingness to embrace ideologies and behaviors that set themselves in destructive opposition to goodness, beauty, and truth. Hence, as my former professor, David Wells, once wrote: “worldliness is anything that makes sin seem normal and righteousness seem strange.”

In the end, this much seems true: A Christ-like church must be both for and against “the world.” Yet the more important point is that this dual posture cannot take any form we wish: Our antagonism must always be housed within a larger protagonism.

Carnes puts it like this:

“the ‘versus’ of the church and world is enfolded into a larger for-ness. . . . There is a kind of against-ness: God did not leave the world to its own deterioration and destruction; God placed God’s own body against the forces of sin and death. And yet how could this story be told apart from the larger protagonism . . . which begins with a God who ‘so loved the world’?”

If you get nothing else, get this:

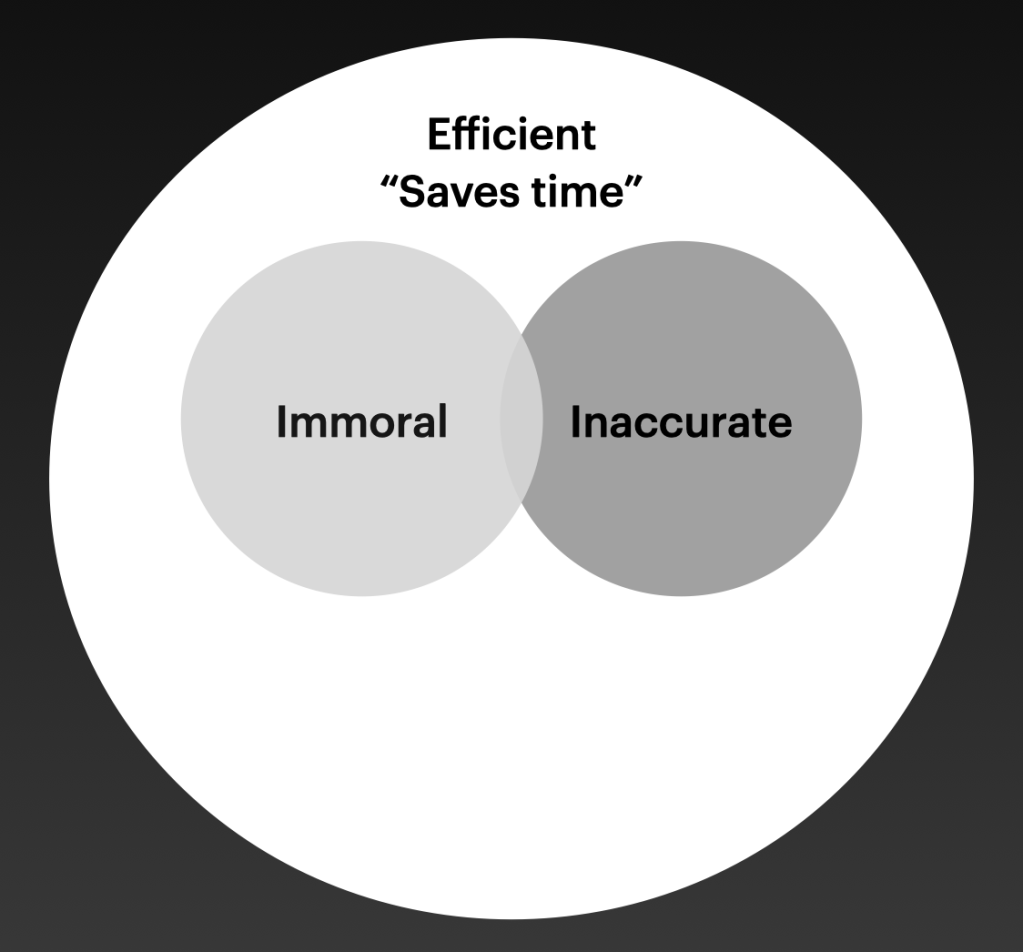

- A church bent primarily on defeating the world inevitably becomes more like it.

On the other hand…

- A church bent only affirming the world inevitably ceases to be “for it” since we have nothing to offer that the world does not already have.

The first point explains why rigid and partisan forms of religious fundamentalism often harbor and hide some of the darkest sins (see here)–whether sexual abuse, excusing and elevating authoritarian leaders, and even forms of violence. The second point explains why many exclusively pro-world (“affirming”) churches are basically empty. Why go? Especially when there’s golf and sleep and football.

We need both points, for as Carnes notes, “the world” is not merely something “out there” but “in here” with the dividing line running not only between groups, denominations, or political parties—but through every human heart, including mine.

Thus, Paul gives this crucial reminder not to pagans but to Corinthian Christ-followers who have lost the plot: “though we live in the world, we do not wage war as the world does”-i.e., with violent, snarky, flailing, win-at-all costs power plays (2 Corinthians 10:3).

Conclusion

If this were my classroom, I’d grab a marker and try to illustrate a better model for envisioning the church-world relation: beyond strict division or simplistic overlap (see below), and toward a complex and mysterious layering that sets aside combat metaphors in favor of more agricultural ones–since Jesus used those too. Something like this:

In one sense, I am borrowing from Saint Augustine, who says it this way:

She [that is, “the pilgrim City of Christ the King”] must bear in mind that among [her] very enemies are hidden her future citizens; and when confronted with them she must not think it a fruitless task to bear with their hostility until she finds them confessing the faith. […]

In truth, these two cities are interwoven and intermixed in this era, and await separation at the last judgment.

~De Civitate Dei, 1.35

Hello friends. Please subscribe on the home page to receive these posts by email. This is especially helpful since I’ve decided (mostly) to uncouple the blog from social media. I’m grateful for you. ~JM

![[Indistinct chatter]](https://joshuamcnall.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/pexels-photo-704555.jpeg?w=700&h=430&crop=1)