This is the final post in a three-part series on the mortal human body in two classic works of literature: Homer’s Iliad and Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. Though the topic may seem morbid, it grants an opportunity to reflect on God’s continued care for “this earthly tent” even after death, and to reclaim The Great Books as conduits for Christian formation.

Now… allow me to share something I don’t like about the handling of this subject in the Iliad, and how Dostoyevsky helps.

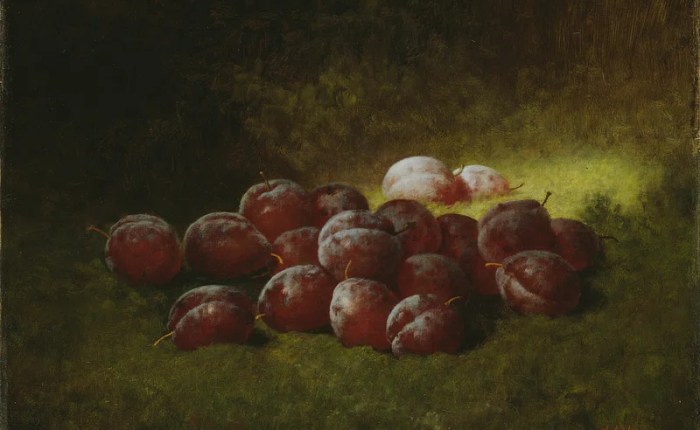

An Odor of Decay

One of the more brilliant and poignant moves by Dostoyevsky in The Brothers Karamazov involves what happens to the body of the saintly Elder Zosima.

Zosima is, in many ways, the voice of Christian love within the work. And as he nears death, many expect some great miracle to accompany his soul’s departure. Perhaps the corpse will smell of lavender and be miraculously preserved. Perhaps the heavens will portend some sign of triumph and approval. Perhaps (like Elisha) his remains will work great wonders to convert the scoffers and the skeptics.

But none of this transpires.

Dostoyevsky patterns this part of The Brothers Karamazov on the traditional Russian construction of a saint’s life (zhitie), where a holy person’s relics perform signs or withstand decomposition.

Yet shockingly, for Zosima, his corpse almost immediately emits a terrible stench of fleshly corruption: an odor of decay that sets in far faster than normal.

To quote the KJV in its description of Lazarus: “He stinketh.”

The scene was so scandalous Dostoyevsky had to beg his publisher not to censor it, and he implores his editor to leave in the more jarring Russian word for “stank.”

The expedited smell of rot causes some to declare Zosima a false teacher. And the combination of rumors and self-righteous gloating from his enemies drives the story’s hero, Alyosha Karamazov (Alexey), to question his faith, reach for a glass of vodka, and head off to visit a woman of ill repute (Grushenka) who has designs on debauching the young monk.

From Homer to Dostoyevsky

I bring up this strange happening because I find it to be a helpful counterbalance to a trend I spoke of previously (here and here) in Homer’s Iliad.

In Homer, the gods always dole out special treatment in who gets cared for both before and after death. Great warriors and the sons of deities get extra care and preservation, as when “Apollo pitied Hector, and kept his body free from taint.” Meanwhile, the rest of us rot.

When a spear is hurled at the mortal child of a god or goddess, it gets bumped off course by a nepotistic divinity. But it never clatters harmlessly to the sand. It always skewers some poor schmuck standing just behind the target.

Life still feels like that sometimes. The powerful and privileged get special treatment. And they have special resources to keep them “well preserved” despite the fact that death still comes.

But not with Zosima.

So why does Dostoyevsky tell his story this way?

Why does the saint emit an odor of decay in The Brothers Karamazov, whereas Homer keeps his main characters lemon fresh until the funeral pyre is lit?

The answer, I think, has to do with Dostoyevsky’s own wrestling match with faith and doubt in a world where God’s presence isn’t always discernible. And it hows his tenacity to cling to resurrection hope even when “the gods” don’t provide proof of their affections.

The Other Alexey

The epigraph for The Brothers Karamazov is a quote from John 12:24:

“Very truly I tell you, unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds.”

It is, in many ways, the key that unlocks the entire novel.

Though Dostoyevsky names his hero Alexey Fyodorovich, the ghost of another Alexey hovers over the story’s most painful questions: the author’s three-year-old son (Alexey Fyodorovich), who died just before the book was written, of the epilepsy inherited from Dostoyevsky.

In many ways, The Brothers Karamazov is a father’s raw attempt to work through crushing grief and anger while refusing to relinquish gritty Christian hope. “Unless a seed falls into the ground…,” you can almost hear him reciting as he hammers out his tale of fathers and sons, faith and doubt, death and longed-for immortality.

If the problem in Homer is that the gods intervene too much (and too capriciously), the worry in Brothers is that God might not exist at all, or that he has much to answer for in creating a world where children suffer, die, and then decay.

There is a reason why Job was Dostoyevsky’s favorite book of Scripture.

Bow and Kiss

I’ll teach through Brothers this year in a special class on Christian worldview, offered in the OKWU Honors College.

The goal is to examine some of the biggest human questions through the lens of deeply Christian work of literature—which, when read slowly and discussed deeply (without smartphones or chatbots to give our brains “the odor of decay”), has the capability of forming us more fully in Christ’s image.

So back to the question: Why does Dostoyevsky make his saintly elder stink in excess of nature?

No answer is given.

But several clues are important.

First, Zosima’s last act before dying is to bow and kiss the earth (the place where seeds must fall and decompose in order to bear fruit).

Second, upon going to the alleged prostitute (Grushenka) in his bitter grief, Alexey and the woman do nothing unseemly. Instead, her compassion over Zosima’s death and Alexey’s lack of self-righteous judgment of her past end up transforming both characters—so that neither is ever the same. (Dostoyevsky clearly wants us to notice that this spiritual “fruit” would never have sprung forth except from soil fertilized by the “miracle” of Zosima’s premature decay.)

Third, when Alexey goes next to stand vigil by the Elder’s body, the passage being read over the casket is John 2: the wedding feast at Cana. Here, wine is miraculously made by Christ from water. And what is such wine? It is the product of expedited(!) fermentation that—in John 2—causes the disciples to put their faith in the Messiah.

Thus, even decomposing matter is transformed into fertilizer for an unexpected harvest that far exceeds the single seed.

Conclusion

What I love about Dostoyevsky’s treatment of the mortal human body is his gritty ability to hold together resurrection hope with a world that still smells with the odor of decay.

Whereas Homer’s vision is both formulaic and fatalistic (special people get “preserved” but none get resurrected), Dostoyevsky’s mind is open to surprises that are simultaneously more painful, mysterious, and hopeful.

“Bright sadness” is the paradoxical description that is often used.

Or to steal an oft-quoted line from the Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenas, they tried to bury us, they didn’t realize we were seeds.

Hello friends. Please subscribe on the homepage to receive these posts by email. This is especially helpful since I’ve decided (mostly) to uncouple the blog from social media. Thanks for reading. ~JM