“It’s fun to be somebody’s god, for a little while.”

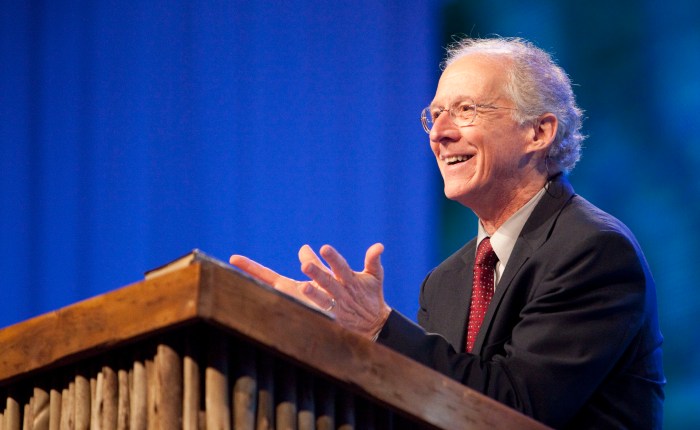

I still remember hearing that line from the lips of a well-known Christian pastor.

It has truth to it. I’ve felt it in rare moments. And he meant it as a warning.

To be a person’s “god” is to be the proverbial frog in boiling water: The hot tub is luxurious, until it cooks you.

In a few months, this same famous pastor would resign amid a cloud of scandal.

In his case (unlike some recent ones), the charges were not of sexual misconduct, but of ego run amok, a lack of accountability for someone deemed “too big to fail,” and a tendency to use celebrity as a “Find and Replace” for integrity when the cameras were switched off.

On second thought, perhaps it’s not so different from the recent sexual scandals involving well-known church leaders.

A common denominator (to misquote Eisenhower) is what I’d like to christen as “The (evangelical) celebrity industrial complex.”

A MUST-READ

In one of the more important blog posts of the year, Andy Crouch submits that it’s time for evangelicals especially to reckon with the insidious danger of celebrity power (Read here).

The reason for the “reckoning” is noted in his Introduction.

In three separate cases [this week] in my immediate circles, a person with significant power at the top of an organization, each one a subject of flattering major media exposure during their career, was confronted with allegations of sexual misconduct and related misdeeds.

All three were […] seen as among the most exemplary Christian leaders of their generation.

Since the article, still more allegations have surfaced against the most famous of these leaders—and he has since resigned while not admitting guilt.

Several of these charges come from high-profile female leaders, one a former CEO of Zondervan, alleging that the well-known pastor pressured them to bring wine and meet alone with him on his private jet, his private yacht, and his private beachside vacation home.

Like Crouch, I choose not to name the leader for at least two reasons. First, I do not know if the allegations are true. And secondly, to focus on the “Name” may be to perpetuate one aspect of our problem: a fixation on the famous people and their escapades: their yachts, their private jets, their beachside villas.

It sounds like a Jay-Z song.

Like it or not, the church is hardly different than the culture in its celebrity addiction. And the culture is rife with it.

One need look no further than the contexts from which we now choose our leaders–The Apprentice, The Terminator, The Oprah.

Crouch again:

In the Oval Office of our country sits a man [… who] is simply brilliant at manipulating the power of celebrity.

He has colonized all of our imaginations—above all, one suspects, the imaginations of those who most hate him, who cannot go an hour in a day without thinking about him.

HOW CELEBRITY POWER IS UNIQUE

But wait a minute; aren’t all forms of authority prone to such corruption? “Power corrupts,” said Lord Acton, “and absolut… [yada, yada, yada].”

True enough. Yet Crouch makes a key distinction between institutional and celebrity power, especially as the latter is now driven by technology and social media.

Celebrity combines the old distance of power with what seems like its exact opposite—extraordinary intimacy, or at least a bewitching simulation of intimacy.

It is the power of the one-shot (the face filling the frame), the close mic (the voice dropped to a lover’s whisper), the memoir (the disclosures that had never been discussed with the author’s pastor, parents, or sometimes even lover or spouse, before they were published), the tweet, the selfie, the insta, the snap. All of it gives us the ability to seem to know someone—without in fact knowing much about them at all, since in the end we know only what they, and the systems of power that grow up around them, choose for us to know.

Crouch’s claim is that “institutions” of power have been largely replaced by individuals—celebrity leaders—whose charisma is both branded and broadcast (via technology) in order to achieve an illusion of intimacy with millions of followers.

Yet in this process, we create idols who behave like monsters—in part, because they both crave and (ironically) resent the fame now thrust upon them.

“It’s fun to be somebody’s god, for a little while.”

“DEAR BROTHERS” ~BETH MOORE

As proof, note how the problem with sexism (and sexual misconduct) often interfaces with the cult of celebrity within the evangelical world, as in others.

Hear the powerful words of the conservative Bible teacher Beth Moore on the subject (here):

About a year ago I had an opportunity to meet a theologian I’d long respected. I’d read virtually every book he’d written. I’d looked so forward to getting to share a meal with him and talk theology. The instant I met him, he looked me up and down, smiled approvingly and said, “You are better looking than ____________________.” He didn’t leave it blank. He filled it in with the name of another woman Bible teacher.

While this sounds almost tame compared to the exploits of Weinstein and Cosby, it still raises questions for the average, decent person.

“Who talks like this!? What kind of person thinks this is an appropriate way to begin a conversation, let alone with a woman, let alone with a preacher, let alone with a female preacher you have never met!?”

Answer: a celebrity.

Because part of the business of fame is the conscious and unconscious learning that you get special treatment.

“When you’re a celebrity they let you do it. Grab them by the __________.”

ANOTHER KIND OF POWER

There are exceptions of course.

Not all celebrities leverage fame toward abusive or destructive ends. And it’s easy to be critical from the cheap-seats. After all, who’s to say how celebrity would affect me?

“It’s fun to be somebody’s god,” until it isn’t.

One point, however, is how different this pursuit of fame and famous people differs from the way of Jesus. At various points in the Gospels, Christ was thrust onto the very cusp of (ancient) celebrity.

In John, after feeding five thousand people, we learn that the crowds had decided to “make him king by force” (Jn. 6.15).

This, after all, is one way celebrities are minted—almost without the permission of the one cast into the limelight. In some cases, a gifted and talented individual wakes up to find (almost to their chagrin) that they have been made into the “face” of an industry or movement overnight, without ever intending to be.

“I never asked for this,” they think – “I was just trying to speak truth, make art, or craft music.”

Too bad.

You’ve been made “king” by force. And the only way off the ride is to push the self-destruct button.

Or is it?

Christ chose a different path. He didn’t self-destruct exactly, but he did intentionally put the kibosh on the celebrity sausage-maker (a very unkosher metaphor).

After this same miracle, he says the following:

I am the bread that has come down from heaven. […] Unless you eat my flesh and drink my blood you have no part in me.

The publicists stopped calling after that one.

And the next time they “made him king by force,” it involved a crown of thorns.

Throughout the Gospels, Jesus flees the crush of the adoring crowds in order to pursue more meaningful relationships, to pray, and to reenter the region of obscurity. Prophets are made in the wilderness, after all, not on the red carpet, and not in the Twitter-verse.

Crouch:

The visible image of the invisible God left no portrait. The one time he wrote, he wrote in the dust (Jn. 8.6). He had a different way of using power in the world, a way that turned out to outlast all the emperors, including the Christian ones.

He offered no false intimacy—his biographer John said that he entrusted himself to no one, because he knew what was in every person’s heart (Jn. 2.24 –25) —but he kept no distance, either.

He let the children come to him. He let Mary sit at his feet and let another Mary wash his feet with her tears. Hanging naked on a cross, he forgave, blessed, and made sure that yet another Mary would still have a son.

His power, truly, was not of this world.

If there is a solution to the evangelical celebrity industrial complex, it’s in reclaiming this strange kind of power.