Every story needs a villain.

And in much of the Christian tradition, that character is unquestionably the devil.

In recent days, I’ve been focusing my energy on a non-blog-related project: a book on the atonement. And the present chapter has to do with Satan. This sounds like a strange topic for the Christmas season. Yet the Scriptures connect it explicitly with Christ’s coming. As 1 John writes:

“The reason the Son of God appeared was to destroy the devil’s work” (3.8).

Yet while belief in God is quite common throughout our culture, belief in Satan does not rank nearly so highly.

As the late Walter Wink put it, the demonic is “the drunk uncle of the twentieth century.” We keep them out of sight. And we don’t talk about them at dinner parties. As he goes on:

Nothing commends Satan to the modern mind. [He is] a scandal, a stone of stumbling, a bone in the throat of modernity.

As evidence, a recent Barna survey indicated that around half of American Christians do not believe in the devil as a living being. Rather, they tend to see him as a mere symbol for profound evil.

REVIVING “OLD SCRATCH”

In response to this, Richard Beck, in his new book Reviving Old Scratch, describes the modern experience somewhat like the plotline from an episode of “Scooby Doo.”

STAGE ONE: At the beginning of every episode, whatever evil that had transpired was blamed on some sort of ghost or goblin. The supernatural was everywhere! And it was up to no good. Beck calls this Stage One, or the period of “enchantment.”

STAGE TWO: Yet after some investigation by Scooby and the gang, it was invariably discovered that the “ghost” was really “Old man Cringle” with a fog machine, a bed sheet, and some fancy voice modulation. Beck calls this Stage Two: the age of “disenchantment.” And as he argues, it has much to commend it. After all, science has shown that many ancient superstitions were just that.

STAGE THREE: Yet in Stage Three (not included in the Scooby Doo episodes), Beck argues that we need a kind of “re-enchantment” if we want to account fully for the pervasive nature of evil in this world. In his view, this is not a simple return to a belief in a demon behind every bush. But nor is it the peculiarly modern (white, wealthy, and western) superstition of full-fledged naturalism.

TWO DANGERS

In his own way, C.S. Lewis proposed something similar. As he wrote:

There are two equal and opposite errors into which [we] can fall about the devils. One is to disbelieve in their existence. The other is to believe, and to feel an excessive and unhealthy interest in them.

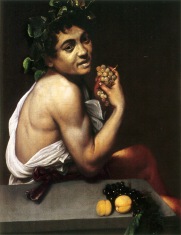

The unhealthy interest is encountered in various forms. One is the tendency we all have to demonize our opponents, detecting whiffs of sulfur in their presence. Case in point:

Or as Beck writes:

We always smell sulfur around those we want to kill.

A second form of unhealthy interest comes when Christians use Satan as an excuse to cover their own faults.

Along these lines, I recall once being in a meeting in which serious allegations (and serious evidence!) were brought forth regarding misconduct. When confronted, one leader responded that “This is just Satan getting angry because we’re doing such good work!”

Sometimes sulfur masks our own scent.

Thirdly, Satan can be wrongly used as a tool to terrify people into compliance, as seen in the Christian cottage industry that springs up around Halloween to scare the “heck” out of unsuspecting sinners as they wander through a warehouse version of the afterlife.

Such moves confuse a love of Jesus with fear of torture.

Finally, an excessive interest in “the devils” can lead to a dualism that puts God and Satan on (almost) the same level. This is not the biblical portrait. For as Luther wrote of Satan–and perhaps enacted by hurling his ink well at the devil–“one little word shell fell him.”

LOVE IS AN EXORCISM

Yet while “excessive interest” carries pitfalls, unbelief does too.

It does nothing to stop the march of minions. For as Wink notes: Disbelief in Satan did little to prevent him running roughshod across corporate boardrooms and bloodstained battlefields throughout modernity.

What is needed, Wink suggests, is a kind of exorcism, though not the kind from horror movies. In his words:

The march across the Selma bridge by black civil rights advocates was an act of exorcism. It exposed the demon of racism, stripping away the screen of legality and custom for the entire world to see.

What’s more:

The best “exorcism” of all is accepting love. It is finally love, love alone, that heals the demonic. “How should we be able to forget those ancient myths about dragons,” wrote Rainer Maria Rilke, “who at the last minute turn into princesses that are only waiting to see us once beautiful and brave?”

CONCLUSION

In the end, Wink’s work (and even the above quote) shows forth certain faults. In particular, he demythologizes far more than I would, and his views on Christ, creation, and atonement are hardly biblical in certain respects.

Nonetheless, he did do the academy a great service by restarting the conversation on evil powers, and by showing how spirituality interlocks with political, psychological, and social forces of all kinds.

If you’re interested in reading more, try the following: