Recently, I’ve begun reading The Chronicles of Narnia to my daughters. You must do this as a Christian parent, or you forfeit your credentials. So I comply.

Fortunately, Lucy and Penelope love the books, and I’ve enjoyed the change from Disney princesses whose primary aim is to meet a man and live in a castle.

We just finished Prince Caspian, and near the end, Aslan arrives to help the Narnians. In gratitude, the spirits of the trees begin to dance, and all the creatures join together in a raucous celebration. It’s basically a rave, minus the Molly and the techno.

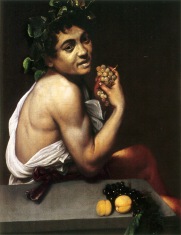

The party is led by a figure known as Bacchus.

He appears as

a youth, dressed only in a fawn-skin, with vine-leaves wreathed in his curly hair. His face would have been almost too pretty for a boy’s, if it had not looked so extremely wild. You felt, as Edmund said when he saw him a few days later, “There’s a chap who might do anything – absolutely anything.”

WHO IS BACCHUS?

Unbeknownst to my daughters, Bacchus (also called Dionysus) is the pagan god of wine, fertility, and wild parties. The Latin translates to “Kardashian.”

For the Greeks, his symbol was the phallus, and he was accompanied by a throng of women, the Maenads, who danced and sang around him. The Maenads also make the trip to Narnia.

As Lewis writes:

Bacchus … and the Maenads began a dance … and where their hands touched, and where their feet fell, the feast came into existence.

Thus Aslan feasted the Narnians till long after the sunset had died away, and the stars had come out … And the best thing about this feast was that there was not breaking up or going away, but as the talk grew quieter and slower, one after another would begin to nod and finally drop off to sleep with feet towards the fire and good friends on either side.

It sounds fantastic. Yet the question is why Lewis decided to have the pagan Bacchus lead the celebration of the Christ-cat.

The fundamentalist internet knows why.

INTERNET OUTRAGE!

It turns out, C.S. Lewis was a closet pagan, whose true desire was to turn your children into tiny Satanists. It’s true; I read it on a blog with multi-colored font (see: “homemakerscorner.com”). And who could doubt it, for as the blogger writes:

What Lewis is describing here is nothing other than a Bacchanalian orgy!

(Well, yes, minus the sex.)

The post goes on:

C.S. Lewis was a master of combining … heathen myths to develop his plots. Worst of all, this is for children! … It’s too bad nobody ever explained to him the consequences of such behavior. … Perhaps he would not have cared. Perhaps he had a known “calling” for his father the devil which he was willingly fulfilling.

And “homemakers corner” is not alone.

A quick Google search finds many sites, some even with monochrome font, decrying Lewis’ debauchery, his paganism, and what’s worst: his similarity to J.K. Rowling (*makes sign of the cross).

So why did Lewis do this?

SAVING BACCHUS

Three points:

First, it is clear that Bacchus’ Narnian revelry has been reformed in crucial ways. Thus there is no mention of sexual looseness, drunkenness, or pagan worship.

Second, it is also clear that Lewis’ view of the party god is hardly uncritical, for he has Susan say to her sister:

I wouldn’t have felt very safe with Bacchus and all his wild girls if we’d met them without Aslan.

Third, and quite important, is Lewis’ belief that even paganism got certain things right about the divine, even though they got other things dreadfully wrong (See Till We Have Faces; also Paul in Acts 17).

Indeed, what the Maenads knew, far better than Ned-Flanders-Christianity (TM), is that with the divine comes festival joy. Consider, for instance, how many of Christ’s parables involve parties. And consider also the critiques of Pharisees against him.

Thus, one of Lewis’ goals throughout his writings is to show that true delight is not tamped down, but rather found in Jesus. As he famously wrote in The Weight of Glory:

It would seem that our Lord finds our desires not too strong, but too weak. We are half-hearted creatures, fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us, like an ignorant child who wants to go on making mud pies in a slum because he cannot imagine what is meant by the offer of a holiday at the sea. We are far too easily pleased.

Given this, Lewis’ point is not to elevate the Greek god of parties, but to show that true mirth is found in Aslan’s presence.

As I heard someone say once:

I seriously doubt that Christians will have much to say to the world until we can learn to throw better parties.

That’s true, and it has nothing to do with embracing drunken licentiousness.

LORD OF THE WINE

But why use Bacchus?

This, of course, is the objection from the rainbow-fonted internet.

Why not create a less phallo-centric mythological creature to deliver this lesson, like a talking cucumb… (okay, bad example) tomato, a talking tomato?

One last point:

Interestingly, it may be that the selective nod to Bacchus was not original to Lewis.

It may trace back to Christ himself.

In John 2, Jesus’ first miraculous sign is not the healing of a leper, the raising of the dead, or the restoration of lost sight. Instead, it is the creation of over 120 gallons (!) of the headiest wine imaginable—enough to overflow three bathtubs—and this, to keep a dying party from going dry.

There is much symbolism here, but as Tim Keller notes in the best sermon I have heard on the text (here), one intended echo may have been the Dionysian tales of the hills running with wine and revelry.

In this miracle, Christ was showing himself to be the true Lord of the Wine, and the true bringer of festival joy.

This matters, as Keller says, because most people reject Jesus for the wrong reasons. They do so, because they fear that it will cost them mirth. Yet as both the Psalmist and the Maenads knew, in the presence of the divine

“there is fullness of joy; at your right hand are pleasures forevermore” (Ps. 16).

And while one may say this with a talking tomato, I prefer Lewis’ approach.