In-keeping with my claim that reading is rereading, I spent an evening recently flipping through Alan Jacobs’ excellent book, The Year of our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in an age of Crisis.

He notes how, in a time of total war, an assortment of Christian poets, novelists, and philosophers produced some of the most remarkable and enduring work of the century. The players include Jacques Maritain, W. H. Auden, C. S. Lewis, Simone Weil, and T. S. Eliot.

More interesting still was that these folks were neither pastors nor theologians, and they did not focus explicitly on current events (i.e., the latest headlines), though the geopolitical world was quite literally on fire.

Instead, they turned to the humanities and education—poetry, novels, philosophy, and habits of prayerful contemplation—as ways of rebuilding the ruins of a fallen civilization on a more robust foundation than merely the desire to “save” civilization.

Perhaps civilization has been imperiled, wrote C. S. Lewis in 1942, “by the fact that we have all made civilization our summum bonum [highest good]. And “Perhaps civilization will never be safe until we care for something else more than we care for it.”

Many of them also identified a malignant common thread between the likes of Hitler, Stalin, and even many within the allied powers: a technocracy of domination, devoid of humane religious and moral underpinnings.

As Auden wrote, in a paragraph on “techinique” and “temporal power,”

“What fascinates and terrifies us about the Roman Empire is not that it finally went smash but that . . . it managed to last for four centuries without creativity, warmth, or hope.”

Or Jacques Maritain in Education at the Crossroads:

“Technology is good, as a means for the human spirit and for human ends. But technocracy, that is to say, technology so understood and so worshipped as to exclude any superior wisdom and any other understanding than that of calculable phenomena, leaves in human life nothing but relationships of force, or at best those of pleasure, and necessarily ends up in a philosophy of domination. A technocratic society is but a totalitarian one.”

Or C. S. Lewis:

“What we call Man’s power over Nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument.”

LESSONS FROM THE RUBBLE

Jacobs’ point is that each of these writers (despite deep differences and numerous blind spots) strove with astonishing energy—at what might seem the least convenient time—to throw a lifeline to their readers in the form of deeply literate and thoughtful form of Christianity, which was neither a withdrawal from the public square, nor a breathless regurgitation of political talking points. “I see no hope for the Church,” wrote C. S. Lewis, “if it allows itself to become just an echo for the press” (or government).

Thus, if one wants to learn what a faithful form of cultural rebuilding looks like, we would do well to consider their examples.

Here then are Jacobs’ concluding lines—which seem more needed now than ever:

“If ever again there arises a body of thinkers eager to renew Christian humanism they should take great pains to learn from those we have studied here”

SIGNS OF LIFE

I revisited the book, in part, because Jacobs just announced his coming retirement from the Honors College at Baylor University. Still, as he heads off to (hopefully) write more books, there are signs that small pockets of this kind of thoughtful and historically-rooted Christian education are beginning to bear fruit.

The work isn’t sexy, and it won’t garner headlines, but it is happening in small corners even now.

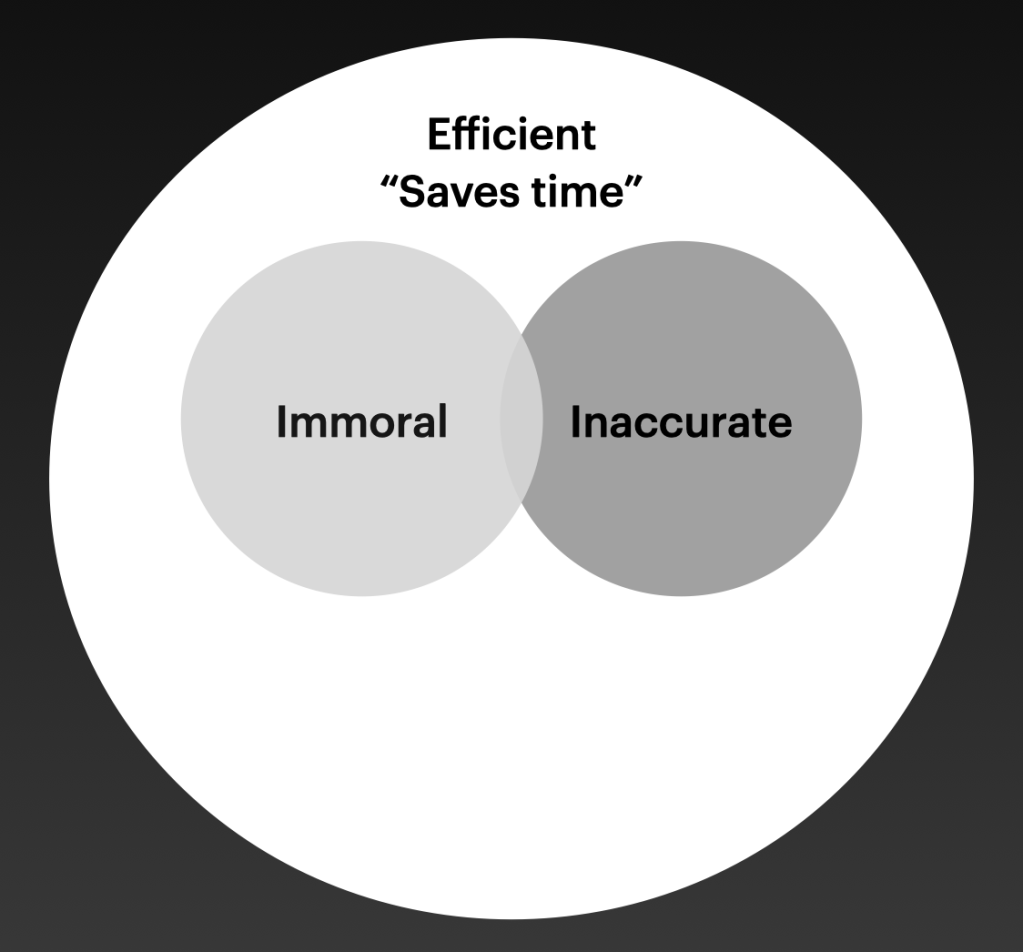

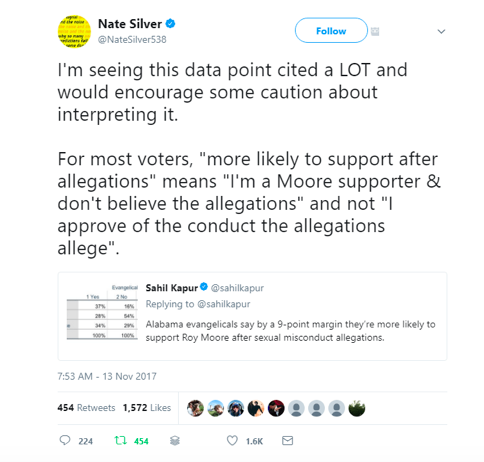

Case in point: This Spring, twelve students signed up to take an Honors College class with me on Dostoevsky and discipleship, as witnessed in his brilliant but difficult novel, The Brothers Karamazov. The students come from a host of majors—accounting, biology, ministry. Most don’t need the course to graduate, but they’ve been convinced, partly by my soapbox evangelism, that the way through life’s toughest questions is more likely to run through the Great Books than by machine-gunning prompts into Chat GPT.

Evidence 2: Last week, I drove down to Oklahoma Baptist University to learn from one of their Honors seminars in which college students meet at 8am each morning (roughly 4am “CST” [College Student Time]) to discussGreat Books from a Christian perspective. The class was excellent. Not a smartphone in sight. Books and notebooks open. Insightful conversation. It was led by a church history professor, and the program is overseen by Oklahoma’s former poet laureate, Ben Myers.

Evidence 3: As I thumbed through a catalogue of books due to come out soon on the topics of theology, the arts, and culture, it was striking to see how many of those authors had been shaped and trained (in some way) by what might be called the “Baylor pipeline” in which Alan Jacobs has served for years within their Honors College. I am under no illusions (whatsoever!) that Baylor is a perfect place. Still, at least one pocket there has become quiet but consequential hub of deep and humane Christian learning, tucked within a Big 12 school.

All that to say, take heart.

For in the words of Auden, though “our world” seems “Defenceless under the night,” still, “Ironic points of light / Flash out whereever the Just / Exchange their messages.” And so,

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame

Hello friends. Please subscribe to these posts via the button on the home page to receive future posts by email. This is helpful since I’ve decided (mostly) to uncouple the blog from social media. I’m grateful for you. ~JM