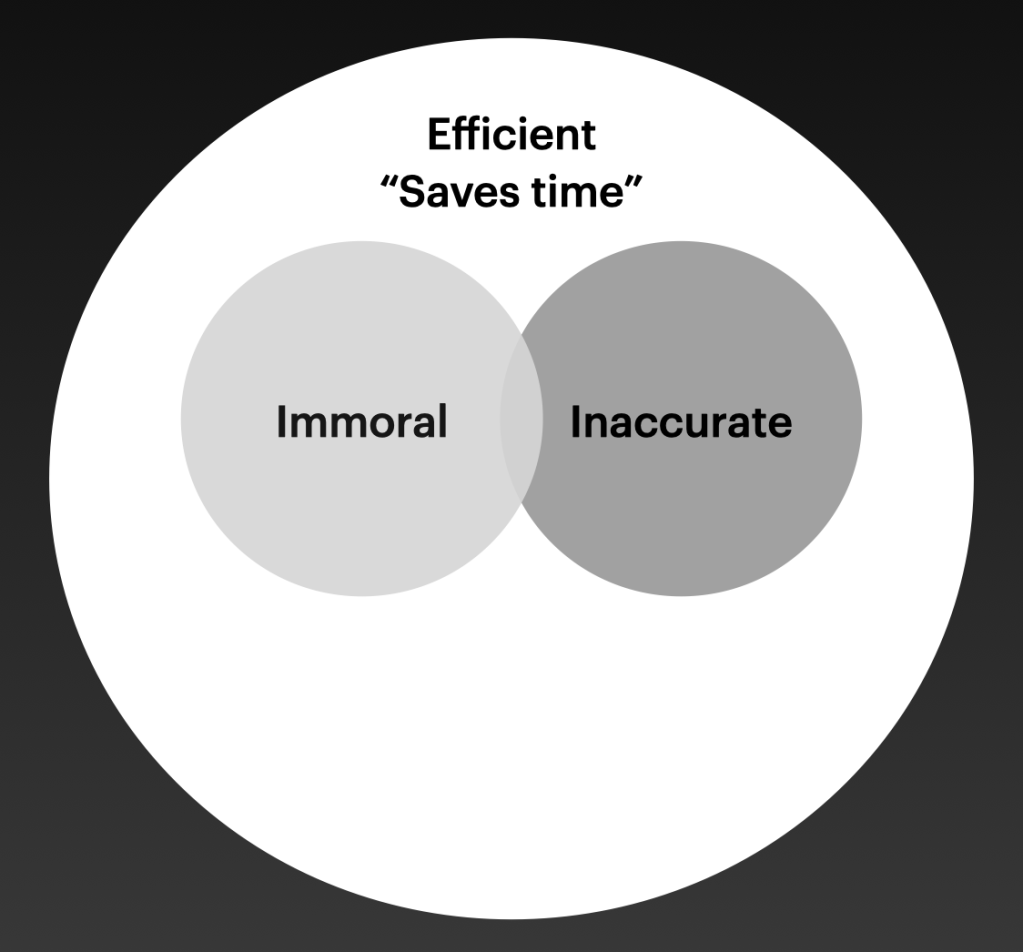

I created a Venn diagram recently to articulate when I think use of AI is ethical and when it’s not.

The smaller circles represent ways in which use of AI is problematic, while the remaining white space illustrates helpful ways in which one may utilize it to save time or accomplish meaningful tasks.

I want to be clear on two points: First, I do use programs like Chat GPT for some things. So I am not proposing a blanket rejection. And second, my focus here is almost exclusively on LLMs (Large Language Models) used to generate text and language. Thus, I am not interested in other ways that AI may be helpful, say, in coding, accounting, or other areas of life. My focus is on words.

My question is a simple one: When do programs like ChatGPT contribute to the good life, and when do they make me dumber, less personal, and less capable of being formed into a thoughtful and connected human being?

Let’s start with efficiency. As Jacques Ellul famously warned, the modern pull of “technique” tempts us to reduce every aspect of life—including relationships and spirituality—to a question of efficiency. In essence, if it saves time, do it.

Of course, efficiency may be a good thing. I do not ride a donkey to the office. I own a dishwasher. And I do not etch my writing on wax tablets. Broken, inefficient processes can be both frustrating and blameworthy. However, there are times when the modern idolatry of efficiency causes harm to others and ourselves.

Allow me to explain:

Circle #1: Efficient but Immoral: The most obvious way AI-use becomes unethical is when our drive to save time leads to immoral choices. Case in point: When I ask students not to use ChatGPT for a particular assignment (because I want them to think and grow by wrestling with ideas and words), to do it anyway is cheating. True, they may not get caught. But it is wrong nonetheless. Likewise, if my church expects me to write my own sermons (as they ought to… ), if I outsource an undo amount of that reflection to a robot, I am in the realm of immorality.

Frankly, many immoral decisions (whether robbing a bank or visiting a prostitute) are driven partly by our thirst for efficiency, which is to say, the drive to get something as fast as possible with the least amount of effort. And in these cases, the fact that it “saves time,” is hardly an excuse.

Circle #2: Efficient but inaccurate: A second problem with AI is the proliferation of falsehoods, inaccuracies, and other bogus depictions of reality. That’s because while programs like ChatGPT do a great job of producing grammatically correct sentences, they do not necessarily prioritize truth.

Hallucinations abound. And evidence is not hard to find: Sites like Google now prioritize bogus AI images of real animals, even when they look nothing like the actual creatures being searched.

LLMs invent sources that don’t exist, as attested by a friend of mine who was surprised to find his own name in footnotes, listed as the author of numerous academic works that don’t exist. And by some accounts, it’s going to get worse.

As Ted Gioia argues,

“Even OpenAI admits that users will notice ‘tasks where the performance gets worse’ in its latest generation chatbot. …

This isn’t a flaw in AI, but a limitation in the training materials. The highest quality training sources have already been exhausted—so AI is now learning from the worst possible inputs: Reddit posts, 4Chan, tweets, emails, and other garbage.

It’s going to get worse. Experts believe that AI will have used up all human-made training inputs by 2026. At that point, AI can learn from other bots, but this leads to a massive degradation in output quality.

In other words, AI will soon hit a brick wall—and face a dumbness crisis of epic proportions. That will happen around the same time that AI will have pervaded every sphere of society.

Are you worried? You should be.”

I can’t say whether all of this is accurate. But it further raises the specter of “the bogus” at a time when we are already drowning in it.

Circle #3: Efficient but impersonal: Now for the saddest (and weirdest) one.

As I watched the 2024 Olympics on Peacock with my kids, one of the commercials that ran on maddening repeat was the now infamous “Dear Sydney” ad for Google Gemini. The premise is bizarre. A dad asks AI to write a fan letter on behalf of his daughter to the American sprinter, Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone: “I’m pretty good with words,” he intones, “but this has to be just right.”

Responses to the ad were a mix of confusion coupled with a collective gag reflex. WHO IN THEIR RIGHT MIND WANTS AN AI-WRITTEN FAN LETTER!?? pretty much summed it up. Or in the words of Alexander Petri, that ad “makes me want to throw a sledgehammer into the television every time I see it.” After all, how do you possibly ruin the universally endearing act of a child authoring an imperfect but adorable note to her hero? Hey Gemini, can you help with that?

Google isn’t alone. I heard recently of a dad who asked ChatGPT to write the speech for his daughter’s wedding. And I personally received an 10-page email from a stranger, asking me to answer a list of questions about one of my books, The Mosaic of Atonement. For a small-time author, letters from readers can be encouraging (and sometimes not). But this one ended with an admission saying that it had been composed by AI. To be clear, the sender hadn’t bought the book. He hadn’t read the book. And he hadn’t even taken time to WRITE THE EMAIL he had sent me. Still, he wanted me to write a long response. (A friend suggested that I plug his 10-page email into ChatGPT and ask for a 10,000 word reply in Klingon.)

My claim for this third circle is simple: We should reject AI in instances where more genuine human interaction and personal attention is reasonably expected. That’s not every use of words (as when I asked ChatGPT to help me smooth out the legal jargon in an insurance claim after my car was totaled… [I repent of nothing!]), but it does require us to discern what parts of life cannot be delegated without a loss of love and human care. As L. M. Sacasas writes, “attention has moral implications.” (And that includes fan letters, sermons, and your daughter’s wedding speech.)

The potential cost is high: In addition to someone wanting to throw a sledgehammer at you, our epidemic of loneliness will continue to creep into domains normally immune to it. After all, as C. S. Lewis wrote, “We read to know that we are not alone.”

Circle #4: Efficient but infantilizing: For those who care about education and formation, this may be the most important circle. Admittedly, “infantilizing” is probably not the best word for it, but it speaks to the fact that education and discipleship are meant to move us toward maturity. And on that point, L. M. Sacasas seems right to note that the most important question to be asked of any technology is, “What kind of person will this make me?”

That is, how will this use of AI shape me?

In the humanities especially, to labor slowly over words, sources, and ideas is—without question—the best way to grow as a thinker and communicator. Believe me, the work is slow and often frustrating. But it changes you in ways that cannot be accomplished otherwise. Somewhere in his five million published words, Saint Augustine remarks that “people will never know how much I changed my mind by writing.” That sentiment resonates for me—in part, because I read and wrestled with it as I wrote a PhD on Augustine’s theology. That work changed me, tedious though it was.

In at least some cases, when we outsource the labor of thought and articulation, we move backward on the scale from Idiocracy to Augustine—which is a pretty fair diagnosis of many ills that currently afflict our cultural, political, and spiritual lives. (Let the reader understand.) The grammatically correct sentence is not the goal of writing. The goal is a well-formed and mature person.

In the words of Alan Noble, teachers must attempt to convey that

“the process of writing, when done well, is working magic in their minds, making them into better thinkers, better readers, better neighbors, better citizens. That writing will help them know themselves and others around them. But that writing will also take hard work, just as all good things take hard work. And to use AI to help with that hard work will rob their minds of all those good things. It would be like going to the gym to lift weights only to have someone come along and lift them for you. You’ll never grow stronger. You’ll never grow. You’ll only waste your time.”

Perhaps this case feels like a losing proposition. So be it. A final lie from the idol of efficiency is that only “successful” tasks are worth undertaking.

But for teachers and pastors especially, when it comes to the case for wisdom in our use of technology, the words of T. S. Eliot (in “East Coker”) still echo over the wasteland of soulless bureaucratic prose:

“For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.”

For further reading on this topic, the folks cited in this post are excellent: Alan Noble, Ted Gioia, Alan Jacobs, and L. M. Sacasas.

Hello friends, thanks for reading. Please subscribe to receive future ones by email. This is especially valuable to me since I’ve decided not to promote the blog much on social media these days. I’m grateful for you. ~JM