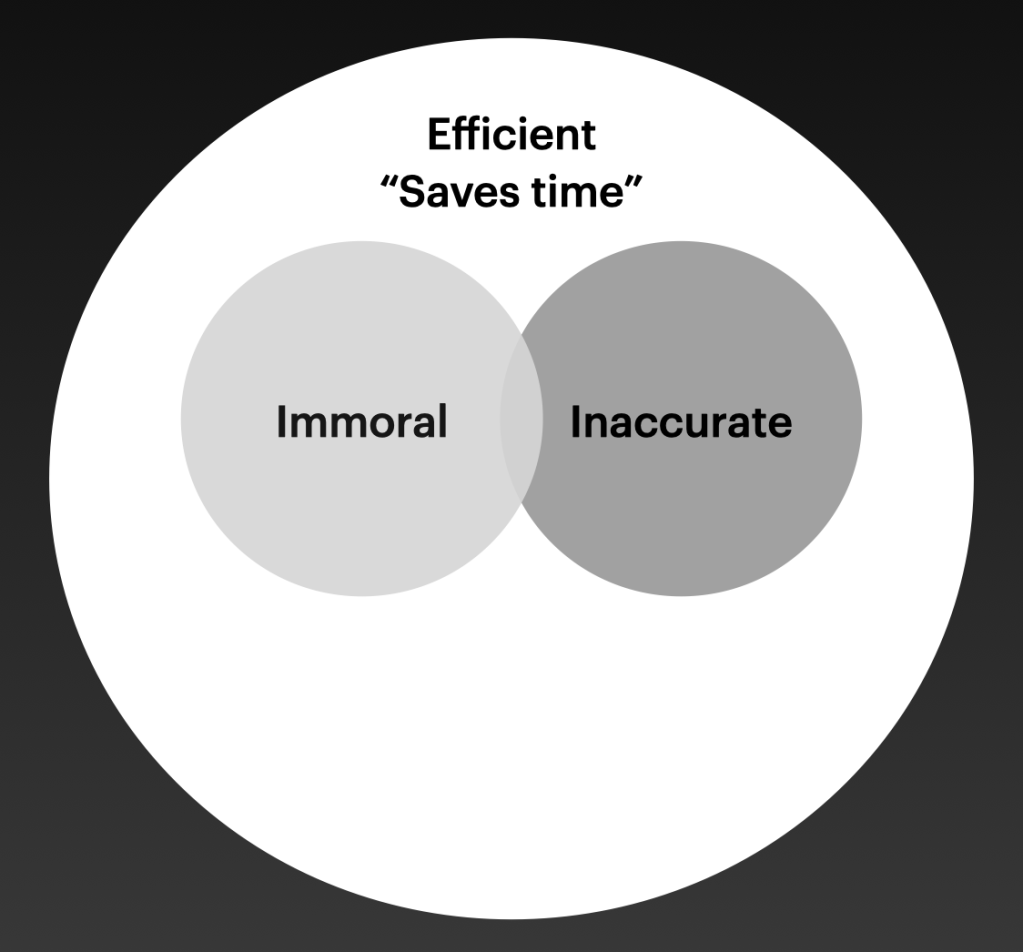

“If I ever write a book about technology and modern life, that will be the title.”

I said that to my wife recently as we were watching Netflix. We were using closed captions since the kids had just been banished to their rooms. And during the course of the episode, I was struck by how one caption appeared more than any other, entombed in brackets: [Indistinct chatter].

And now that I’ve mentioned it, perhaps it will stand out to you as well.

It appears everywhere on the shows we consume: In crowded restaurants, on bustling streets, inside Dunder Mifflin, in Ted Lasso’s locker room, and virtually everywhere else.

You might “indistinct chatter” is the soundtrack of our lives.

In a literal sense, and especially for the hearing impaired, the caption alerts viewers to a constant buzz of unintelligible and unimportant speech, humming somewhere in the background. But the more you think about it, the more it starts to feel like a kind of oracle or prophetic diagnosis of what ails us in our age of noise and news and social media. Who’s speaking? We can’t say. What language? IDK. What makes this wave of jumbled words more consequential than, say, the noise made by my neighbor’s lawn mower? Nothing, really.

Still, the caption-generating gods of Netflix feel compelled to include them in a font that is just as large and bold as actual dialogue, lest we miss this apparently important detail. And in a weird way, that’s basically my goal here. Have you noticed how much of modern life can be summarized by what’s in those brackets?

You could take that observation in a dozen different directions.

But here are two quick attempts at showing why it matters.

When words become white noise

First, we become so accustomed to indistinct chatter—unintelligible and unimportant words that wash over us almost constantly—that we find it hard to function without it. The chatter soothes us. Silence is unsettling. And we cannot bear to be alone with our thoughts. Eventually, washing dishes, driving a car, or even using the restroom become unthinkable without a verbal (or visual) security blanket of incessant, often vacuous, noise. Air pods, tik tok, twitter. You hear it now.

I’ve seen the effects of this especially in college students who say they cannot read, focus, or do homework without various forms of media running constantly in the background. This too is indistinct chatter. Though “Background TV” is another for it. And despite some obvious benefits—dampening the noise across the hall, or making one feel less alone within an empty apartment—psychologists also caution that our addiction to such electronic noise carries costs: We use it to drown out inner monologues that need attention, and we may eventually find ourselves unable to follow more complex arguments, conversations, or plot-lines since our word-diet is now filled with empty calories. Reflection becomes difficult. And idiocracy encroaches further.

Only the shrillest are heard

Second, to be noticed in a world (or news cycle) of constant chatter requires one to shout–or perhaps to make a scene. Subtlety is lost. And eventually, poets, preachers, and reasonable politicians are replaced by demagogues and provocateurs.

Before we know it, our cultural Caps Lock remains constantly illumined like the faulty tire pressure light upon your dashboard. After awhile, you don’t even notice it. We are seeing the cost of this now in our shared political lives especially, where (to quote Yeats), “the worst are full of passionate intensity,” while the rest are just really, really tired.

So what’s the solution?

As usual, the way forward begins by noticing the way that caption has come (metaphorically) to dominate our lives. In the words of Andy Kennedy,

Every great solution starts with someone noticing a problem. Noticing is underrated. Notice more. Good things will follow.

But noticing is not enough. We must also make decisions, at least periodically, and for sustained intervals to unplug from machines and environments that threaten to drown us in indistinct chatter.

Here though is an irony. As I write this, I am seated outside by the fire while robins and bluejays and large group of black crows are performing their own bit of background noise. It too is unintelligible. Yet it hits differently than a steady stream social media alerts, breaking news, doom-scrolling, calendar reminders, and the targeted ads that constantly assault us. Is it chatter? Of a sort. And yet.

As the Psalmist writes:

There is no speech nor language, where their voice is not heard.

Their line is gone out through all the earth, and their words to the end of the world. In them hath he set a tabernacle for the sun,

Which is as a bridegroom coming out of his chamber, and rejoiceth as a strong man to run a race” (19:3-5 KJV).

Which is to say, go touch some grass. And for just an hour, disable captions.

Hello friends. Please subscribe to these posts via the button on the home page to receive future posts by email. This is helpful since I’ve decided (mostly) to uncouple the blog from social media. I’m grateful for you. ~JM

![[Indistinct chatter]](https://joshuamcnall.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/pexels-photo-704555.jpeg?w=700&h=430&crop=1)